Inside the wooden cabinets are shelf upon shelf of herbarium specimens. Originally written by: Jie-Mei Li (graduate student, School of Forestry and Resource Conservation) & Professor Xiao-Wei Yuan (Chair, School of Forestry and Resource Conservation)

At the corner of Royal Palm Boulevard and Palm Avenue, standing quietly behind rows of hoop pine, is an old building belonging to the School of Forestry. Built in 1959, the building has seen students pass, year after year. As one enters a nondescript room on the third floor plainly marked “Specimen Room”, one is actually walking down the corridors of history. Within its modest exterior, the Specimen Room harbours a wealth of Taiwan’s natural history and agriculture: around 100,000 specimens, over 800 type specimens, and even Taiwan’s earliest herbarium specimen, dating from 1792. Buried away in a peaceful corner of the NTU campus, the Specimen Room tells a captivating story.

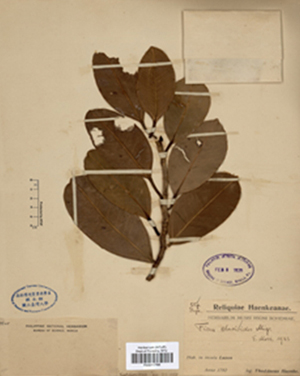

The oldest known plant specimen among the Specimen Room’s collection: a specimen that Czech botanists, Thaddaeus Haenke, collected from Luzon, Philippines in 1792. The piece was later identified as the Ficus clusioides Miq. by American botanist Elmer Merrill in 1933. As the wooden door swings open, the eye is confronted with rows of wooden cabinets. Inside the cabinets are shelf upon shelf of herbarium and fruit specimens, most of which have been collected by the faculty and students of the School of Forestry and Resource Conservation. There are also plant specimens collected by Professor Tyôzaburô Tanaka, who served at the Department of Horticulture during the Japanese Colonial Era. The faculty and students of the School of Forestry have continued to collect and exchange specimens.

The Specimen Room, which is currently curated by Professor Chung Kuo-Fang, has a magnificent collection that, together with the Herbarium of Taiwan Forestry Research Institute and the Botanical Specimens Hall in NTU’s School of Life Science, is classed as one of Taiwan’s three great plant specimen collections. If we go deeper into the Specimen Room, we may discover the 1792 specimen from the Philippines which was discovered by Librarian Guo-Xiong Wang while he was processing the digital archives. Taiwan’s oldest known specimen goes back to 1854 and was collected by Scottish botanist, Robert Fortune. But in the room itself, we can find specimens that go even further back in time.

Tracing the historical records, Mr. Wang discovered that the specimen from the Philippines was discovered by a collector towards the end of the 18th century, and it was only later that Tyôzaburô Tanaka came into its possession when exchanging specimens with others for research. In addition, the Specimen Room also holds a type specimen that pre-dates even Taiwan’s oldest specimens as it was brought from India in 1835.

Standing in the Specimen Room, one feels surrounded by the flood of history—these specimens are of an age that far surpasses our years. By comparison, our own concerns seem rather insignificant.

The oldest known type specimen among the Specimen Room’s collection: Scottish botanist Robert Wight’s No. 492 specimen, an isosyntype of the Olea linocieroides, collected in 1835 from Courtallum, Southern India. Tyôzaburô Tanaka was one of the finest scholars in Taiwan during the Japanese Colonial Era, but in 1944 he retired from Taihoku Imperial University (forerunner of NTU) and returned to Japan. Thus, a highly talented scholar left at the height of his academic career—a great loss for both the university and Tanaka himself. In 1945 Japan ceded Taiwan following its defeat in the Second World War, and it was only in 1958 that Tanaka returned to Taiwan in the hopes of retrieving his library, his manuscripts and the more than forty sketch books he had filled with drawings of numerous species of tangerines from all corners of the world over the course of almost 30 years. But owing to Japan’s military defeat and enemy status, the library had been confiscated and, becoming the property of National Taiwan University, was lost to Tanaka. Moreover, the sketch books and manuscripts had long been lost or mislaid, so Tanaka returned home with nothing. He thereby remarked helplessly, “What a pity! So many treasures, and yet I return empty handed.”

And yet, in a stroke of luck more than fifty years later, as Mr. Wang was sorting the specimens, he noticed that several of the items were connected with Tanaka. A search of the records showed that they had been stored in classrooms in the Department of Horticulture at Taihoku Imperial University, and then moved to the Specimen Room in the School of Forestry around 1960. Tanaka’s private collection of almost 30,000 specimens had all been contained in the Specimen Room collection. As the items were digitally archived one by one, a number of valuable specimens emerged.

Tanaka started collecting early, at a time when large quantities of plants were being classified by botanists all across the world and type specimens were the basis of botanical taxonomy. At that time it was not understood that type specimens were what gave value to a specimen collection, but his method of exchanging or buying specimens led Tanaka to inadvertently obtain many early valuable type specimens.

The moment of discovering the Tanaka collection in the Specimen Room is like the moment you see an oyster open its shell to reveal a shining pearl. The thrill of the discovery drew Mr. Wang onwards, to go deeper, and to discover what other treasures the Specimen Room might contain. Mr. Wang had been working in the School of Forestry Specimen Room for just over a year, yet because of a lack of funding and human resources, he had to single-handedly sort through all the specimens: re-labelling, checking documentation and archiving them one by one. Fortunately, the staff and students helped out by doing repairs and maintenance, publicizing the room and so on, enabling Mr. Wang to concentrate on dealing with the specimens.

While processing Tanaka’s collection, Mr. Wang realized that it was not only very old but also contained specimens from several important botanists, including several hundred specimens and dozens of type specimens from renowned botanical taxonomist Robert Wight, whose specimens also constitute a major part of the collection at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in the UK.

A display of Tyôzaburô Tanaka’s collection of liquid preserved citrus specimens The School of Forestry’s Specimen Room has had the good fortune to possess Tyôzaburô Tanaka’s specimens due to another important figure, Professor Tang-Shui Liu. Liu was a former member of faculty who, during his time as head of the College of Agriculture, had Tanaka’s collection removed from the classrooms of the Department of Horticulture at Taihoku Imperial University and moved to the Specimen Room in the School of Forestry. When Mr. Wang was sorting the specimens, he discovered that a group of the collection that had been sent to the Specimen Room were somewhat overlooked. On consulting the historical data, Mr. Wang surmised that because Tanaka had not yet published anything on these specimens, there was no way to trace them back to him. After the specimens were moved, Professor Jih-Ching Liao was sorting through unlabelled specimens for his research and suspected that they dated from the Japanese Colonial Era. After being compared to Tanaka’s unpublished manuscript and documents containing his classification numbers, it was deduced that these specimens may have been gathered by someone connected to Tanaka.

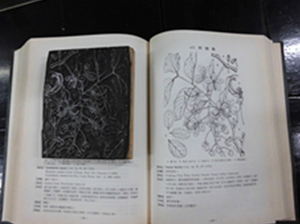

Professor Liu also arranged seeds and fruit specimens one by one in a glass receptacle. Each time one opens a cabinet, one finds another treasure. For example, the metal cabinets by the wall are full of plates (i.e. for illustrations in printed books) that Liu commissioned Chien-chu Chen to create. But as the somewhat outdated facilities made it difficult to control temperature and humidity levels, the plates have corroded and turned green. Thankfully, the lines of the plates can still be made out and they can be compared with past printed editions to determine the exact shapes, which can also be an interesting activity.

Prof. Tang-Shui Liu’s arrangement of seeds and pine specimens in glass receptacles  One of the many joys in the Specimen Room is identifying images in the book with its corresponding mouldboard.  Prof. Tang-Shui Liu’s manuscript under an image of an Apiaceae Hydrocotyle plant The lack of precise control over the temperature and humidity levels of the Specimen Room environment has not just corroded the printing plates but has also had a highly deleterious effect on herbarium specimens. The difficulty of raising funds to improve the site means that staff can only apply for small sums for maintenance and modest equipment updates, rather than a major overhaul; so for all their historical significance, the advanced age of the specimens means that they often simply fall to bits. Thus, when sorting the specimens, Mr. Wang proceeded with extreme care for fear of damaging or even erasing a piece of history.

Among the collection, a manuscript written by Professor Liu on the China fir, an old wooden cabinet which appears in Tanaka’s books, and photographs and several of Tanaka’s pickled specimens were also discovered. These historical relics give us an insight into the careful and methodical approach of scholars in the past—an example we would do well to follow today.

Digging deeper, one finds that new treasures are continually cropping up. Upon opening a cabinet, roll upon roll of illustrations emerge, all hand-drawn pictures of plants. These illustrations were created before projectors were prevalent, and such drawings were indispensable classroom teaching materials. Seeing them now, one cannot help but marvel at the tremendous drive and energy of teachers in those days.

The School of Forestry set up the Specimen Room in order to preserve these traces of history. All the staff and students have worked together to promote the room and raise funds for its upkeep. It is like an oyster, patiently secreting layer after layer and finally producing a shining pearl. In this way, even in midst of the hectic metropolitan lifestyle, there is still something that endures. As we continue down the road of history, we shall not lose sight of the past.

References

Ming-Der Wu & Ping-Lie Tsai (1998). The Writings of Professor Tyôzaburô Tanaka (unofficial translation).

|